It Starts With the Patient: Why Contextual Factors Will Transform Your Practice - Part 1 of 5

When it comes to successful outcomes in physical therapy, most clinicians naturally focus on the technical elements of care: assessment accuracy, treatment techniques, and dosage of exercise. While these are undoubtedly essential, an old adage applies here:

“The best surgeon in the world cannot heal a cut.” - J.M.T. Finney (1917)

The patient does the healing. Our job is to create the best environment for that healing to happen.

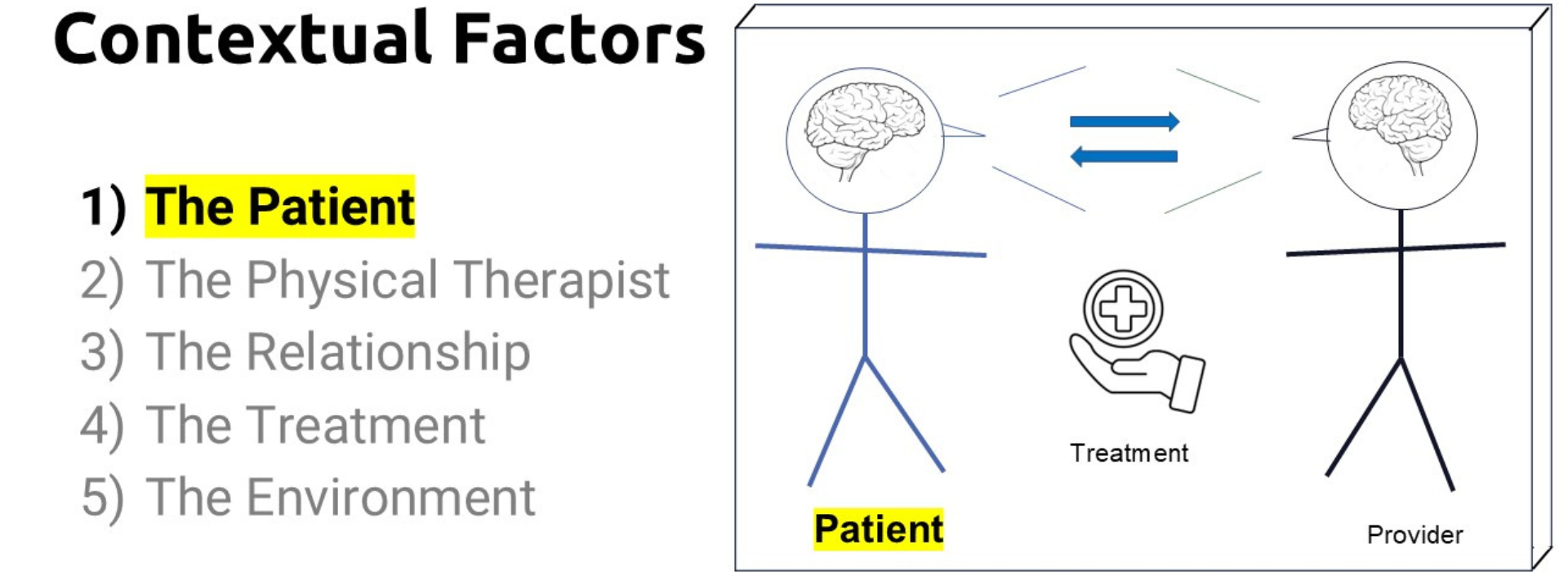

This blog post is the first in our five-part series, Understanding Why Contextual Factors Will Transform Your Practice. In this entry, we’ll explore the patient as a contextual factor: how their beliefs, expectations, emotions, identity, and life experiences shape not only their experience in physical therapy but also their likelihood of a successful outcome. Of all the contextual factors, the patient is uniquely positioned, not as an external influence on treatment, but as the living, responsive agent in whom healing (or lack thereof) ultimately occurs.

The Science Supporting the Patient as a Contextual Factor

Decades of research, including the foundational work by Testa & Rossettini [1], highlight the role of contextual factors and the mechanisms of action in clinical outcomes. Among these, the patient stands apart. Whereas the therapist, the environment, the treatment, and even the therapeutic relationship exist around or between the patient, it is the patient who interprets, filters, and responds to all these elements. Their personal context, their internal “ Map of Reality”, is the lens through which all other factors are processed.

One of the most compelling illustrations comes from a recent scoping review of the mechanisms of manual therapy [2]. Studies show that when patients believe a treatment will help them, it often does, even when the treatment is inert. Conversely, if they expect it to fail, it likely will. Their mindset, in other words, can be as impactful as the treatment itself.

In behavior change research, we also see how critical the patient’s readiness, sense of control, and emotional state are in driving outcomes. When a patient sees themselves as a passive recipient of care, progress often stalls. When they feel like an empowered partner, they engage more fully, adhere to plans, and persist through setbacks [3].

What Makes the Patient Distinct

While the other contextual factors—therapist, therapeutic relationship, treatment, and environment—play important roles, they are external contributors to the therapeutic encounter. The patient is different. They are the central processor of every experience, message, and intervention.

Nothing is neutral. Every part of their aspect of care is mediated by their beliefs, emotions, culture, and readiness.

The therapist may offer a perfectly crafted explanation or intervention, but its effectiveness depends on how the patient receives and interprets it. The environment may be calm and supportive, but if the patient is overwhelmed by anxiety or past trauma, that calm may not be perceived. Even the best treatment will fall flat if the patient is not mentally or emotionally positioned to engage with it. The patient is not just one contextual factor, they are the context in which everything else unfolds.

What the Patient Brings to the Encounter

Understanding the patient as a contextual factor means recognizing and responding to what they bring with them:

1. Beliefs and Expectations

Some patients believe pain equals damage. Others might expect a “quick fix” or hold onto skepticism about physical therapy. Unchecked, these beliefs can become barriers to effective care. Your role is not just to deliver an intervention, but to explore, validate, and, when needed, reshape these beliefs into ones that support recovery.

2. Emotional and Psychological States

Fear, anxiety, depression, and anger are common in patients dealing with pain or dysfunction. These emotional states can modulate the pain experience and reduce motivation. Recognizing emotional cues and responding with psychologically informed communication can improve patient readiness and therapeutic engagement.

3. Self-Concept and Identity

Patients with long-standing pain often experience an identity shift, from active individuals to someone limited by their condition. Helping patients reconnect with their prior sense of self or create a hopeful new identity can be a transformative part of the healing process.

4. Stage of Change

Borrowing from the Transtheoretical Model [3], it’s crucial to know whether a patient is in precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, or maintenance. Your approach to education, intervention, and motivation should align with where the patient is, not where you want them to be.

The Role of the Physical Therapist

In this model, your role expands beyond technician to collaborator, coach, and meaning-maker. This doesn't mean becoming a psychologist, it means recognizing that the therapeutic encounter is both a biomechanical and psychosocial (biopsychosocial) event.

It’s not about making the patient responsible for their outcome. It’s about acknowledging that their participation is an active ingredient in the intervention.

What are the skills you need to support this model?

- Open-ended interviewing to draw out beliefs, fears, and motivations.

- Active listening to validate the patient’s experience.

- Reframing maladaptive beliefs into helpful perspectives.

- Collaborative goal-setting that aligns with patient values.

- Measuring and enhancing readiness to change so that interventions land at the right time.

Real-World Example

Consider a patient with chronic low back pain. She has seen multiple providers, undergone imaging, and was told she has degenerative disc disease. She arrives at your clinic with the belief that movement will cause further harm. Her expectations are low, and her mood is deflated.

A therapist focused solely on technique might prescribe core stabilization exercises with little effect. A therapist who considers the patient as a contextual factor, however, starts by exploring her beliefs. They listen deeply, connect with the frustration, validate her concerns, and reframe the concept of degeneration as a normal part of aging. Doing this skillfully is critical!!

They align treatment goals with what matters to her, such as playing with her kids, and start small to build confidence.

In this case, the intervention isn’t just the exercise, it’s the context created around it. The patient’s new understanding and meaning of pain, her self efficacy and commitment to move forward becomes the real treatment, and it makes all the difference.

Why This Matters Now

With the increasing emphasis on value-based care, patient satisfaction, and measurable outcomes, we must expand our lens.

Biomechanical expertise remains important, but the future belongs to those who integrate the whole human into their clinical reasoning.

The good news? This doesn’t require a radical shift in your practice. It requires awareness, intentionality, and a willingness to lean into the patient’s experience.

A person is a dynamic system of beliefs, emotions, experiences, and behaviors—all interacting within a social and environmental context. Recognizing this complexity allows therapists to identify patterns that shape a patient’s responses to care. This understanding enhances clinical reasoning and guides more personalized, effective interventions. In short: when you treat the patient as a person and not just a diagnosis, outcomes improve. And when you see the patient as the central context—not just one of many factors—you begin to unlock the full potential of care.

What’s Next in the Series

This post is the first of five, each one exploring a different contextual factor that shapes care. Posts will be released every two weeks, opt in to emails below to never miss a release!:

- The Patient (this post)

- The Therapist – How your communication, confidence, and beliefs influence outcomes.

- The Therapeutic Relationship – Understanding and strengthening the alliance.

- The Treatment – How the presentation, delivery, and framing of interventions impact efficacy.

- The Environment – Exploring the physical and social space in which healing occurs.

Missed the Introduction? Read it here

Each installment will include practical strategies, evidence-based tools, and real-world scenarios to help you integrate these factors into everyday practice.

We’ll also be sharing bite-size insights and takeaways on Instagram and LinkedIn to keep the conversation going.

Try this…

As you move forward in your clinical work, begin by reflecting on your own patients:

- What are they bringing into the room?

- What communication strategies are you using to explore their beliefs?

- How are their beliefs, emotions, and expectations influencing the care process?

- What skills do you need to improve to better engage them?

Understanding the patient as a contextual factor is not a theoretical exercise, it’s a practical key to better outcomes. Join us in the next post as we turn the lens inward and examine the role of the therapist in this dynamic equation.

Looking for More?

This blog series is just a small window into the larger framework we teach inside our full course at Patient Success Systems.

If you’re finding this content useful, the course offers a deeper, more structured path. We explore the science behind contextual factors, break down communication strategies, and provide practical tools you can use to improve outcomes—day in and day out.

Whether you're new to these ideas or ready to refine your skills, the course is designed to meet you where you are and support your growth as a clinician who leads with thoughtfulness and precision.

👉 Learn more about the full course here.

Because when you strengthen the context around care, everything changes.

- Testa, M., & Rossettini, G. (2016). Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo: How contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes. Manual therapy, 24, 65-74.Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1984). The transtheoretical approach: Crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin.

- Keter DL, Bialosky JE, Brochetti K, Courtney CA, Funabashi M, Karas S, et al. (2025) The mechanisms of manual therapy: A living review of systematic, narrative, and scoping reviews. PLoS ONE 20(3): e0319586.

- Hickmann, E., Richter, P., & Schlieter, H. (2022). All together now–patient engagement, patient empowerment, and associated terms in personal healthcare. BMC health services research, 22(1), 1116.

- Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American journal of health promotion, 12(1), 38-48.

Join Patient Success Systems!

Simply sign up below to get the latest delivered to your inbox.